- Home

- Susannah Stapleton

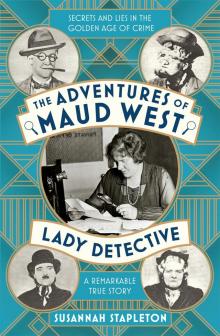

The Adventures of Maud West, Lady Detective Page 6

The Adventures of Maud West, Lady Detective Read online

Page 6

Of all the Maud Wests I had found in the census and other sources, none had leapt out as being definitively my Maud, although three had caught my eye for various reasons. The first was a suffragette from Maida Vale who had been bound over following a riot that had broken out after Emmeline Pankhurst’s very public arrest at the London Pavilion in July 1913.25 Although one of her fellow rioters ‘emphatically denied that hat-pins had been used’, it had been quite a violent scuffle and I could imagine Maud getting stuck in for the cause.

The second was the daughter of an Irish QC, called Dorothea Maud West, whose worthy spinsterhood seemed so pitifully dull that I could only hope that she had led a secret double life. She was also the only candidate I had found whose background tallied with Maud’s statements that she came from a legal family.26

Finally, as a thrilling outsider, was a Maud West from St John’s Wood, who had been sentenced to four years’ hard labour in 1894 for a string of thefts, which included over £1,000 worth of diamonds. As one newspaper reported:

Absolute defiance was the attitude taken up by Maud West, a tall, well-dressed young woman, who was before Mr Cooke at Marylebone Police Court to answer three charges of robbery – one of an extensive character, and all alleged to have been committed with daring and ingenuity … During the hearing Maud West kept up a running commentary on the evidence, and made a saucy reply when remonstrated with by the assistant gaoler.27

The age was off by a few years, but she undeniably showed the right amount of pluck. Besides, who better to catch villains than a former master criminal?

But, when it came down to it, I had to admit that my shortlist was little more than a wish list. So far, I’d found nothing to pin a detective career on any of them. I kept running into brick walls and was beginning to understand how Maud felt when she popped into that tea shop for a break: barely a month into my research, I, too, felt fatigued, depressed and irritated.

Why was I even bothering? Maud West was a proven liar – and she wasn’t the only one. I’d never encountered so many slippery characters in the course of my work. At times, it seemed that hardly anyone in Maud’s orbit was who or what they said they were. Even Albion House was masquerading as its former self.

Then, during a head-clearing walk, it came to me. It was so obvious, why hadn’t I thought of it before? I brought up the London Gazette on my phone and typed ‘Maud West’ into the search box. The results were difficult to read on the small screen, but there it was in October 1933, buried in a batch of dry legal notices.28

It began, ‘I, Maud West, of 59 New Oxford Street …’ before descending into a turgid block of legalese. I skipped past all the ‘heretofores’, ‘in lieu thereofs’ and a number of ‘and furthers’, and scrolled down to what I knew was waiting at the end:

Maud West wasn’t a diamond thief, or a suffragette, or the daughter of an Irish judge. She wasn’t even Maud West – at least, not officially until this notice appeared in the London Gazette. Her real name was Edith Elliott.

The Apaches of Saint-Cloud

BY MAUD WEST

The first time I was shot at coincided with my first business appearance in masculine disguise. It was a ‘long firm’ case, and I had been asked to discover where the man suspected to be responsible was in hiding, and also, if possible, find out where the goods had been stored.

What little was known about his movements pointed to him having escaped to Paris, where he was supposed to be living in the lowest dens and consorting with gangs of real Apaches – the toughest of the tough. It seemed quite obvious that if I were to do any good I would have to adopt a disguise. A woman might have excited suspicions and unwelcome attentions. From a cousin I borrowed a suit and cap, and off I went.

For days I lounged round some of the lowest cafés on the outskirts of Paris. Unfortunately, I only took with me one suit of clothes, and I couldn’t very well go into a shop and order another. As it happened, this oversight very nearly wrecked all my plans. Unable to adopt any other disguise I must have aroused suspicion.

One dark night in a street near St. Cloud I was followed out of a café by a gang of men. Hurrying after me they surrounded me in the lonely street, and began using threatening language, while I could see one or two of them pointing revolvers at me through their coat pockets. They were many, I was alone; and in a flash I decided my only course was to pretend utter ignorance of the French language, so to everything they said I answered by shaking my head.

This drove them frantic, and soon they were all arguing among themselves, almost forgetting me in their furious endeavours to find a way of making me understand their oaths and threats. That was my chance. Taking to my heels I ran down the street. As I fled two shots rang out, and I heard the gang racing along after me.

I ran till I was almost exhausted, and then, turning a corner, I came upon the open door of a house. Hurling myself through it, I closed it quietly after me; stood listening as my pursuers dashed past, and turned to find myself in the presence of an astounded French family. I explained things to them, and we became such great friends that whenever I visit Paris now I always go to see them. For their open door I owe my life.29

Chapter Four

They Do It With Mirrors

I have played so many parts in my business life, and represented so many characters, that my friends declare that I’ve forgotten what my real appearance and personality should be!

Maud West, 19261

After all the hours I’d spent in Maud’s company, it felt awkward to start calling her Edith. Presumably there were those who did (all those solicitors and barristers rattling around her family tree, for a start) but I decided to stick with Maud until she did something Edith-ish – and as I turned my attention to the growing pile of photographs I’d found of her in disguise, she was definitely in Maud territory.

So far, in addition to the young man in the tweed cap and a somewhat bloated Charlie Chaplin, I’d tracked down pictures of her as an old woman, a young fop, a bow-tied foreign businessman and, my favourite, a country bumpkin with a gravity-defying beard:2

Two, however, stood apart from the rest. These were a pair from 1913 that showed Maud transforming herself into a man. They were by far the most straight-laced of the set and I was pretty sure that they had been the very first photographs taken of her in disguise.

Unlike her later studio portraits, they appeared to have been taken in a bedroom or dressing room of some sort. The first captured Maud standing in front of a long mirror, wearing a voluminous white shirt tucked into a pair of high-waisted trousers. Her long hair was pinned up into a bun and she was adjusting her tie. In the second, she was fully dressed and staring straight into the camera with one hand in her suit pocket and the other brandishing a cigarette; a hat now covered her hair, and a lens glinted over one eye. I couldn’t find anything to fault in her outfit, from the hat down to her spats, but the end result lacked the ease and humour of her later efforts.

The photographs had appeared in the illustrated magazine section of the Pittsburgh Press on 27 July 1913, accompanying a piece simply entitled ‘Maud West: Woman Detective’. This had reappeared the following week with an identical layout in the San Francisco Call and I had no doubt that further copies would turn up in other American papers, each with the same introduction:

In fiction the woman detective is always young and fascinating; her skill in handling delicate situations and in solving the most puzzling mysteries arouses admiration. She is fearless and knows how to handle an automatic pistol. Prepare to be astonished: greet one in real life!3

What followed wasn’t so much an article as a jumble of anecdotes narrated by Maud herself. She took in many topics, from her enduring love of A. J. Raffles, the amateur cracksman and gentleman thief, to the importance of taking regular rest breaks. One minute she was admitting how she always looked under the bed at night and the next recalling how she’d faced down an irate blackmailer in her office (‘I have my fingers on a pistol now that can spit ten

bullets while you are firing one with that revolver of yours’).

It was so different to the measured, albeit sensationalist, writing I’d found in her first set of articles, published just four months earlier in Pearson’s Weekly. The first of those had appeared under the banner ‘The Adventures of a Lady Detective’ on 29 March 1913 on the women’s page, alongside recipes and tips for getting rid of female moustaches, but the editor soon realized Maud West’s broader appeal and moved the remaining articles to the main body of the paper. They had been well structured and well written, but this piece in the American press was a more rambling affair. What had got into her?

The answer to that question would arrive in due course but, in the meantime, there was another small mystery to keep me busy. In the midst of her torrent of thoughts was the following statement:

I once stayed at the Grand Hotel in Paris for a fortnight as a man. I did not wear a man’s clothing all the time. Only when I was working. It is the easiest thing in the world to disguise oneself at a hotel and yet occupy the same room. I found no difficulty in avoiding the chambermaids as I went in and out.

She went on:

Often I make my changes of costume in my office here. Not long ago I came in at about 5 o’clock as a shabby old scrubwoman, removed all make-up and garments and was at the Ritz Hotel dressed for dinner by 7 o’clock. That is a pretty good contrast.

It was. But then so was this sudden depiction of herself as a master of disguise when compared to her Pearson’s Weekly articles that spring. There, she had touched briefly upon the subject, saying:

I learnt a lot about the art of disguise in my early years … I learnt, not only how to successfully disguise myself by simple and rapid methods, but how to judge if a person I was following was disguised …4

Beyond that, however, she had given it no particular emphasis. Indeed, of the dozen or so cases she shared, only one had involved any disguise at all, and, even then, she didn’t give any clues as to what that might have entailed, other than it needed to fit into a small handbag and be simple enough to adopt quickly in an abandoned cottage by the roadside.5 A hat, maybe?

Yet here she was, lounging around in a smart black suit, languidly drawing on a cigarette, and explaining to the world how vital male costume was to her work. There were times, she said, when disguising herself as a man was the only option, such as when she needed to keep watch on a house or just loiter in the street: ‘The woman, you see, cannot stand about like a man may.’

She had a point. For better or for worse, the details of a woman’s clothing were always noticed. Whether fashionably dressed or deliberately plain, women were subject to split-second judgements about their appearance. The tiniest details lodged themselves in people’s minds. A man’s suit, on the other hand, rarely attracted attention and had the added advantage of allowing ease of movement. As Maud would later recall, ‘the long, flowing skirts of pre-war days were a nuisance …’6

It all made perfect sense, although I couldn’t help wondering why she hadn’t mentioned it before. Maybe she really had graduated from hat-in-a-handbag levels of subterfuge to being able to pass herself off as a man within a matter of months. Or had something happened that summer that inspired her to add ‘Master of Disguise’ to her résumé?

A clue lay in her next appearance in the press. At the beginning of September, she featured briefly in a Daily Mirror article which opened with a series of questions:

Have you bought a bunch of flowers from a flower-girl in the West End of London or ‘helped’ a tramp ‘along the road’ recently? If you have, are you quite certain that you were dealing with genuine members of their respective classes? Have you any proof that the flower-girl was not a duchess in disguise, the tramp a marquis ‘made up’?7

The country, the paper claimed, was in the grip of a ‘disguise craze’. The manager of Clarkson’s, the foremost theatrical outfitters in London, confirmed that they were making up twenty to thirty people a week. Their latest client had been ‘the wife of a well-known member of the Government’ who had made a bet that she could go unnoticed as a parlourmaid at a house where her friends were staying.

‘I have had twenty-five years’ experience of the business,’ the manager said, ‘and I have never known a busier time for disguising than the present.’ Maud’s contribution was a story of a provincial engineer who had disguised himself as a tramp to eavesdrop on a conversation between his wife and her lover in a London park.

Initially, I assumed that the whole thing had been cooked up by the Daily Mirror to fill a few column inches. But, after a few hours of searching through online regional newspapers in the British Newspaper Archive, I found that the people of Britain had indeed been raiding their dressing-up boxes in unusual numbers during the summer of 1913. There was the army officer from Aldershot, for example, who spent a day duping his friends in the guise of a distressed lady motorist, flirting with one over tea whilst the chauffeur was sent to attend to his car.8

Even men of God were joining in the fun. In the Methodist Recorder, one Wesleyan minister described how he had enjoyed a seventeen-day tour of the West Country disguised as a pauper. The sense of freedom had been intoxicating: ‘As we steamed out of Waterloo, I put my head out of the window and reverted to a trick of jubilant boyhood; I couldn’t help it, the occasion seemed to demand some worthy farewell.’9

The burglars masquerading as house painters and thieves as tramway inspectors were nothing new, although the escaped female convict posing as a Spanish countess seemed to be bringing an unusual level of drama to the standard prison break.10 What was more surprising was that the police were joining in. In August, one constable had dressed as an artisan’s wife and wheeled an empty pram around Lavender Hill in an attempt to catch a bookmaker in the act of street betting. Other similar cases included a policeman going undercover as a lady of leisure to trap a bag snatcher on Hampstead Heath.11 The Sporting Times printed a poem on the subject which bore the refrain ‘That’s a rozzer with his old gal’s clothes on!’12

The biggest headlines, however, were reserved for suffragettes, and I suspected that this was where the whole craze had begun. That April, the government had introduced what would become known as the Cat and Mouse Act to deal with the problem of hunger-striking prisoners. As the only alternative was to let the hunger strikers starve to death, the Act enabled the authorities to release such women on licence – and under constant surveillance – before returning them to custody once their health improved.

In the games of cat and mouse that followed, many suffragettes resorted to disguise to avoid recapture, much to the delight of the press. For instance, after being temporarily released from Armley Gaol on 17 June, Lilian Lenton managed to evade the police by dressing as a grocer’s boy and making off in a delivery van. A few days later, she boarded a train for Dundee disguised as a children’s nurse. On arrival in Scotland, she set fire to a castle and a railway station (her personal target being two empty buildings a week) before moving on to Wales. There, she hobbled into Cardiff station dressed as an old woman and caught a train down to the south coast, where she finally escaped to France on board a private yacht.13

It was all, by turns, both thrilling and amusing, but what on earth was going on? The suffragettes I could understand, but what about everyone else? Was the craze symptomatic of some deeper undercurrent in British society? The waters were choppy enough on the surface: on top of the disruptions to daily life by the activities of militant suffragettes, the country was entering its third year of industrial unrest. Strikes and rallies had become common as workers downed tools in one industry after another to demand better wages.

Such turmoil was one of the defining characteristics of the Edwardian age, as the battle raged between old patrician values and new liberal possibilities, but this tension also manifested itself in more subtle ways. By 1913, for example, one could no longer be confident of a stranger’s status simply by how they dressed or behaved. The brash Northern chap might be an

influential industrialist, or the woman posting a letter bomb the daughter of a peer; even the prime minister, Herbert Asquith, had arrived at Number 10 from nonconformist Yorkshire roots. In short, no one could be trusted to stay where they belonged.

Those who found comfort in the old order were understandably alarmed by all this, but for many others it must have held a delicious sense of possibility. The boundaries that had once confined people to their ‘proper’ station in life had become less solid and, with the help of a cunning disguise, anyone could push against those walls and explore life on the other side. With the threat of exposure ever thrillingly present, a gentleman might become a chimney sweep, a docker a duchess, a countess a washerwoman – and, it seemed, a woman detective a monocled dandy.

Looking at Maud’s later work, it was clear that she had learned a valuable lesson in how to promote herself during that summer of 1913. Her comments about disguise, along with the accompanying photographs, had elevated what could have been an interesting profile in a small magazine to an eye-grabbing piece worthy of syndication in some of America’s biggest papers. Over time, she would take each element of that Pittsburgh Press article and improve upon it in her own inimitable style, adding a hefty dose of humour to the photographs she circulated and revamping the original illustration for use in her own advertising (see overleaf ).

Above all, from that point forward, almost every interview she gave would start with her interviewer listing the various characters she had recently adopted.

But was any of it true? I wanted it to be. I wanted to believe that Maud had gone undercover as a sailor, or had spent months frequenting a village disguised as an old woman, ‘ferreting out the facts of a will tangle.’14 I wanted to believe that her very first outing in a borrowed suit and cap had brought her face to face with a gang of Apaches, the infamous dandy hoodlums who had terrorized the people of Paris for decades with their unique mix of savagery and vanity. And I wanted there to be a small room at Albion House crammed not just with wigs and dinner jackets and beggars’ rags, but comedy items, too, such as the ‘somewhat loud plus-four suit’ that Maud said she used when she wanted to draw attention to her presence on a case.15

The Adventures of Maud West, Lady Detective

The Adventures of Maud West, Lady Detective